Hooke started the first entry in his diary with a weather report: in fact it’s possible that recording the weather was one of the reasons for starting the diary, or memoranda, in the first place. Hooke’s first weather report was for Sunday 10 March 1672:

[mercury] fell from 170 to 185. most part of ye Day cleer but cold & somewhat windy at the South–[I was this morning better with my cold then I had been 3 months before] [moon] apogeum–It grew cloudy about 4. [mercury] falling still

Instead of writing the words ‘mercury’ and ‘moon’ (transcribed in square brackets here), Hooke depicted them with their astrological symbols ☿ and ☽ as a kind of shorthand. For me, the interesting thing about this entry is that Hooke’s own life seems inextricably linked with the weather – he inserts a comment about his cold in the middle of his very first weather report. I think this is a clue to interpreting the weather reports, and thinking about why they appear in what quickly becomes a very personal (and messy, subjective, ‘unscientific’) document and not, for example, in a separate log book (which is what he had advocated to the Royal Society in a paper in 1663). Hooke, and his colleagues in experimental philosophy, had very little way of knowing what information was going to be useful for their scientific endeavours; and they couldn’t predict what sorts of things might influence other things – the effect of weather on human health, for example. One way to get around this was to record as much detail as possible when making observations, so that patterns might begin to appear. So perhaps having the weather reports in a place where they were easily comparable with other happenings (such Hooke’s health, or the moon’s apogee) would be more useful than keeping separate tables.

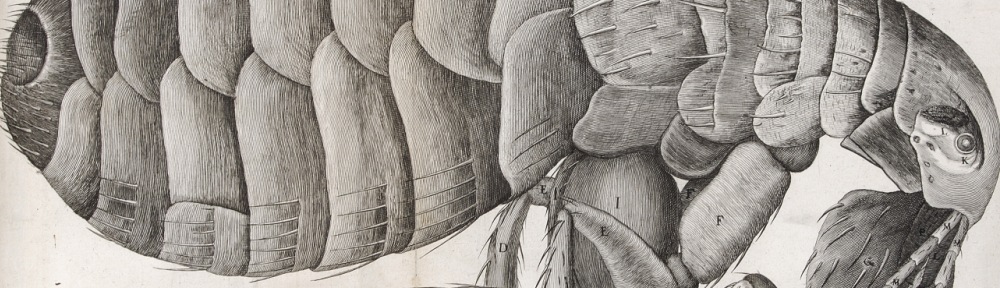

Hooke had several instruments for recording the weather, but the one he mentions most often in his diary is the barometer. Originally an intriguing instrument for making experimental demonstrations about the nature of air and vacuums, the glass tube filled with mercury gradually transformed into a device for measuring atmospheric pressure, named ‘barometer’ by Robert Boyle in 1663. Hooke described his own barometer at length in the Preface to Micrographia. Micrographia of course is mostly (and rightly) famous for its arresting illustrations of microscopic objects, but the text is also fascinating. In his Preface Hooke makes it clear that one of his hopes for science is the improvement of the human senses – all of them, not just sight. For Hooke, the barometer is not merely a device that measures something, it is a way of enhancing human perception of the effects caused by

those steams, which seem to issue out of the Earth, and mix with the Air (and so precipitate some aqueous Exhalations, wherewith ’tis impregnated) . . .

something of this kind I am able to discover, by an Instrument I contriv’d to shew all the minute variations in the pressure of the Air; by which I constantly find, that before, and during the time of rainy weather, the pressure of the Air is less, and in dry weather, but especially when an Eastern Wind (which having past over vast tracts of Land is heavy with Earthy Particles) blows, it is much more, though these changes are varied according to very odd Laws.

He published a drawing of his wheel barometer in Micrographia. The ‘J’ shaped glass tube is filled with mercury, and has a sealed bulb at the top but is open at the other end. In the bulb a vacuum provides enough suction to prevent the mercury from flowing out of the tube. At the open end of the tube a ball floats on the mercury. This float is attached to the pointer on the dial by a length of string. If the air pressure rises the mercury is forced up into the bulb and the level of the mercury at the open end drops. As the float drops too, the pointer moves.

Hooke eventually stopped incorporating detailed weather reports in his diary entries, but he retained a strong interest in the subject. He wrote a treatise about naming clouds, suggesting a standardised system, and he invented an integrated automated weather-recording device that would punch a scroll of paper recording data about temperature, wind speed and direction, and atmospheric pressure. He also continued to note particularly significant weather happenings in his daily entries. On Saturday 11 January 1690 he wrote:

this night about 1 & 2 of the clock was a most violent Storm or Hurrican which blew down trees houses chimny &c. it blew down part of my parlor chimny. vntiled much of my Long garret. broke windows &c. the B[a]rometer was very low vizt horizontall to the right. vpon the falling of Snow between 2 & 3 in the morn the wind ceased it blew at North. N. W. & N. E. the rest of the night and all next day cleer calm cold & frosty

Hooke and his colleagues were setting the tools in place to enable predictions of rough weather on land and at sea. Unfortunately, we’re not able to interpret Hooke’s data because we don’t know enough about his instruments and scales – or at least, I believe that’s the case but if anyone out there knows differently please get in touch!